By Carl Teichrib

Note: Part 2 in the Magical Re-Enchantment series is an adaptation from my book, Game of Gods: The Temple of Man in the Age of Re-Enchantment, pages 171-180.

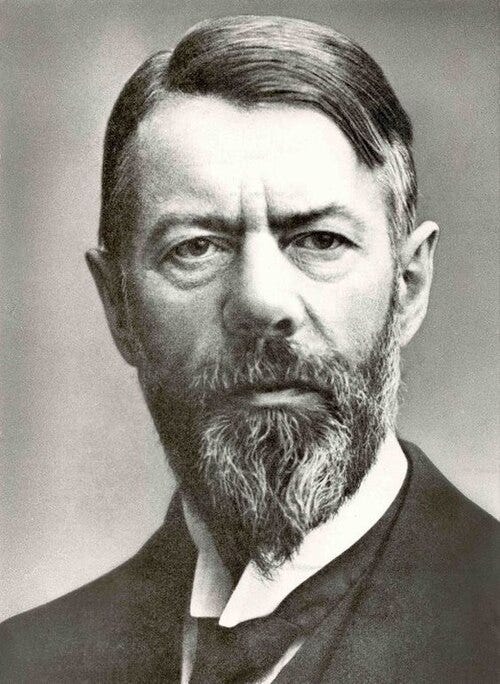

In his 1917 lecture, Science as a Vocation, German sociologist Max Weber noted that the ever-progressive nature of modern science and rationalism had created a condition of disenchantment,

…principally there are no mysterious incalculable forces that come into play, but rather that one can, in principle, master all things by calculation. This means the world is disenchanted. One need no longer have recourse to magical means in order to master or implore the spirits, as did the savage, for whom such mysterious powers existed. Technical means and calculations perform the service.1

Weber had used the phrase “disenchantment of the world” in previous essays on religion. It was language he borrowed from the German Romanticist, Friedrich Schiller,2 adapting it to highlight the tension between scientific rationalism and the historic role of belief. Weber also recognized that the bureaucratic trend, everywhere evident, was clearly derived from technique and the pragmatic character: “rules, means, ends, and matter-of-factness dominates its bearing.”3 Specialization and bureaucracy, he noted, are at odds with traditional cultural moods and aesthetic qualities.

Science had disconnected humanity from mystery and the materialist outlook had eroded the sense of spirit. Thanks to industrialization and technology and urbanization, the masses were increasingly distanced from the toil of fields and forests. Natural struggles and processes were moving into the background. Modernity and secularism had replaced the mythic, displacing wonder and stripping the imagination. We had become disenchanted.

Weber, born in 1864, lived through the intellectual high tide of Modernity. But as explored in my book, Game of Gods, the Enlightenment era and the Modernist epoch also witnessed the inner revolution of Romanticism, new religious movements, and an upsurge in esoteric interests. Secularity had the appearance of social ascension, and it made incredible strides to that end, but spiritual winds were blowing.

Disenchantment sets in motion the desire to replace lost purpose.

In our contemporary milieu – the shift that began in the 1960s/early-1970s and continuing today – what was witnessed is the rejection of Modernity’s claim that science is the “one true description of reality.”4 However, this did not result in a return to Christian thinking. Indeed, there was and remains an overall unwillingness to re-consider the Christian worldview. A societal break from traditionally stabilizing norms was evident, and with this lost mooring the postmodern mind now found itself drifting in a sea of conflicting currents and rising tensions. At the same time, the need for alternative answers to the question of human meaning resulted in a growth market of novel ideas. Postmodernism and the New Age walked hand-in-hand. However, the New Age movement with its spiritualized, Self-focused human potential and its tendency to feast at a thinly-spread spiritual smorgasbord – while profoundly impacting the social landscape with its message of Oneness – was incapable of providing a base narrative that impelled global action.

This does not mean Postmodernism has simmered; the pressure cooker seems to be getting hotter. Nor has the New Age movement disappeared; acceptance is closer to the norm. And the allure of Self-ism, the product of human potential thinking, continues to psychologically validate the pursuit of our own desires: a sign of perilous times – “for men will be lovers of themselves.”5 None of these attributes have dissipated, and yet they failed to offer a path forward – a perceived justification for the re-ordering of a global civilization.

Could something more primal hold the key?

A new context was about to be shaped through an archaic lens, one paralleling Postmodernism and the New Age, yet offering a more robust setting for change. It would recognize the technical while affirming the spiritual, merging Modernism into mystery and the human with the natural. It would be essentially religious, or better said, mythic – powerfully transforming the psyche of Western civilization through a new framing story. However, before considering the scope and role of such an integrating mythology, we need to consider the meaning of myth. Upfront, it is acknowledged that interpretations of what myth is are varied, but for the sake of this discussion, one explanation will be extracted and applied.

Different than, but related to the epic tale, myth explains and exemplifies aspects of perceived reality through the use of symbolic narrative and imagery. Carl G. Jung, who himself was shaped by the 19th century rise of Germanic cultural-spiritual mythology,6 offered this analysis,

The need for mythic statements is satisfied when we frame a view of the world which adequately explains the meaning of human existence in the cosmos, a view which springs from our psychic wholeness… No science will ever replace myth, and myth cannot be made out of any science. For it is not that ‘God’ is a myth, but that myth is the revelation of the divine life in man…7

Eminent scientist and humanist, René Dubos, connected the archaic to the modern in his 1972 book, A God Within,

The myths of ancient peoples are still meaningful to us because they express preoccupations and moods which are universal and eternal… myths change their external appearance when they are adopted by a new culture, but their core of fundamental truth is not thereby altered.8

The “fundamental truth” that Dubos alluded to is the concept of continuity.

Old Testament scholar John N. Oswalt, in his very approachable book The Bible Among The Myths, describes the relationship between myth and continuity this way: “Myth depends for its whole rationale on the idea that all things in the cosmos are continuous with each other. Furthermore, myth exists to actualize that continuity.”9 Thus, the deities of myth are depicted as being dependent on material existence, are driven by necessity, and are bound to external forces.10 Mythic gods and goddesses, contained within the cosmos, reflected the jurisdictions they were associated with – a community of beings existing within and acting upon the cycles and processes of nature. Interdependence was a given.

However, the Biblical narrative, as Oswalt noted, does not qualify as myth for it presents an understanding of reality that is antithetical to continuity. Mythic thinking within the Bible is undeniably evident – the existence of an overarching narrative, the layering of meaning, symbolic richness, supernatural assignments, and ancient religious-cultural themes connected to spiritual living – but its essence remains distinct.11 Whereas myth communicates an interconnected, cyclical view of time and reality – that events in the past have a repeatable quality, and “all that humanity is, the gods are”12 – the Bible presents an atypical paradigm: “a completely different understanding of existence and of the relationship among the realms.”13

God, as revealed in the Bible, is utterly unique and separate from creation and matter. All other spiritual personalities – angelic figures and demonic powers and yes, human beings – are ultimately subject to His laws, and Mankind holds a situational value higher than the animal and plant kingdoms. Time itself is the result of, and is subject to, God’s action upon space and matter; it is therefore linear with a defined beginning and an anticipated point of climax, resulting in a change-over as Jesus Christ “makes all things new” (Revelation 21:5).

Contrasting the ancient pagan worldview – built on the framework of continuity – Israeli scholar Yehezkel Kaufmann explained that the Biblical theme of monotheism points to a deity “who is the source of all being, not subject to a cosmic order, and not emergent from a pre-existent realm; a god free of the limitations of magic and mythology.”14

From the perspective of myth, the three realms – Nature, Humanity, and Deity – operate within a shared reality in which all are mystically bound and interrelated. When this worldview is enacted via ritual, the practitioner is embarking on a trans-personal journey meant to shift one’s sense of time and space, to induce an altered state of mind, and to magically interact with cosmic cycles. Ritual, which can be related to but different than ceremony, is “a sacred drama in which you are the audience as well as the participant.”15 It allows one to “identify with the thing, not sit back and analyze it.”16

The renowned Witch, Starhawk, associates ritual with opening one’s consciousness and connecting to the Divine within.17 It is a psychic and spiritual theater where the All-Self is experienced, stirring the soul as distinctions dissolve and meaning is imparted. Ritual fuses the abstract and tangible, the past and present, the material and ethereal – and it may facilitate communion with supernatural entities, including the gods and goddesses of myth.18

Nels and Judy Linde, respected ritual designers in the neo-Pagan community, tell us that, “Ritual is sacred theater, evoking the principles of belief or faith, reenacting tales of the gods or of myths.”19 Adapting a Jungian perspective, their interpretation of myth and ritual links the ancient to the modern,

Ancient myths that have entered into our common psyche carry the power of the archetypical characters and story inside them, even when we modify the story to suit our ritual purpose. Mythic reference can prepare us to experience spiritual mystery. Even with a different storyline the strength of the original myth can empower the presented symbology.20

Jungian psychologist Stephen Larsen writes: “Myths emerge from, or are contained by, rituals. Rituals are the embodiment of myths.”21

Although the role of ritual in relation to myth is important, it is the aspect of reality narrative we need to consider. In this way, myth serves as a tool to disseminate ideas, embed values, shape worldviews, and emotively position grand themes as representing something sacred and unifying. Myth, understood as an information technology, takes upon itself a propaganda quality and becomes a powerful actor for social transformation.22 It functions as a framing story, not as a tale or fable, but as a way to think and behave.

“The mythic, like any statement,” writes Bill Kinser and Neil Kleinman, “organizes meaning by highlighting and shaping details and by arranging them into a declarative plot.”23

Kinser and Kleinman were describing myth in the context of Nazi Germany. Their overall analysis bears consideration. Take note of the link between narrative, social acceptance, and the development of policy,

Events and situations require explanation. Explanations – universalized, generalized and given imaginative flesh – become myths. Myths shape perception. Perceptions produce policies. Policies cause events and situations. And (to begin again at the beginning) events and situations require explanation. How can one separate the beginning of the circle from the end, the mythic invention from the archetypal situation, or the fabrication from the candid recognition of a geopolitical fact? They share a self-perpetuating cycle. The first feeds the last, and the last vindicates – and reinstates – the first.24

Myth, symbol, theater and drama: Kinser and Kleinman remind us that the power of persuasion, wrapped in a connecting narrative, can refashion social order and remake Man’s image of himself.

In the 1970s, Ervin Laszlo, a renowned systems theorist directing a Club of Rome research project, firmly articulated that a psychological restructuring – the sculpting of minds – was crucially needed for world transformation.25 Although the Club of Rome was known for their technocratic modeling, the Goals in a Global Community research report stressed the reshaping of values and beliefs. One contributor emphasized the creation of overarching social narratives: “New images or myths are needed that will be able to act as guiding images of social change.”26

Cultural targeting would be critical,

Western, developed countries, are among the best initial candidates for the mythmaking project. The countries of this area will be required to make some significant, and sometimes drastic, shifts of perception in order for the ‘new international order’ to be fulfilled. Thus it is very important for these societies to make changes in their value systems. In addition, a shift in values in these societies should have a great impact on the rest of the world… The Western countries, therefore, appear to be very good candidates for the reception of myths about a global society.27

The Stanford Research Institute (SRI), located on the southwest side of San Francisco Bay and recognized as one of America’s leading research centers, was considering new images, too.

During the 1970s, SRI explored models for social evolution as part of a program initiated by the US Office of Education.28 Willis W. Harman – an early LSD researcher29 and the first official lecturer at Esalen30 – was the SRI project supervisor, and visionary professor Oliver W. Markley its director. Reviewers and advisors included Ervin Laszlo, mythologist Joseph Campbell, René Dubos, Margaret Mead, Carl R. Rogers, John White from the Institute of Noetic Sciences, and Timothy Leary’s collaborator in The Psychedelic Experience, Ralph Metzner.31 Each contributor had “a deep appreciation for the profound ways in which myths and images affect the perceptions and actions of humankind in the universe...”32

The project report was publicly released as Changing Images of Man, and it claimed that a fresh vision was coming into focus. Humanity was tipping toward a perennial perspective. The new story of civilization would be interdependence and global community, the cultivating of spirituality and higher consciousness, and a restored relationship with nature. The boundaries of science would expand, producing a “new science of consciousness and ecological systems not limited by manipulative rationality.”33

Similar to Max Weber, the SRI team acknowledged that science had displaced faith, but this had created other issues and concerns. Although science “now performs the cosmological function,” the general public had “little comprehension how scientific knowledge defines the world.”34

Furthermore, scientific materialism had profoundly shaped civil structures, empowering a rigid set of gatekeepers to determine and impart new social values: universities generated knowledge and granted status, industry provided economic reason, government fashioned the larger context, and bureaucracy became enforcers of social order. Humanity was being squeezed into something monetized and managed, and this, the SRI report noted, was a mismatch to the new and emerging image: “disenchantment with the technocratic elite, [and] the decreasing trust and confidence in governments” was evident in the survey data.35 The budding, post-industrial image would be nestled within an organic and networked environment, and institutions would have to adapt to the new paradigm. It was a message that was euphoric, yet controversial.36

The SRI new image would adopt “an ecological ethic, emphasizing the total community of life-in-nature and the oneness of the human race,” and it would entail a “self-realization ethic” focusing on selfhood and human development. Man’s new image must be “multi-leveled, multi-faceted, and integrative,” embracing cultural and personal diversity. Social balance would be key, yet the overall project must remain “experimental, open-ended, and evolutionary.”37 The SRI team affirmed that the new image was itself an old image, stemming back thousands of years, “in the core experiences underlying the world’s many religious doctrines, as reported through myth and symbols, holy writings, and esoteric teachings.”38

Conspicuously absent from Changing Images of Man was a roadmap on how to achieve the celebrated paradigm, although the new image can “be hastened or slowed by deliberate choice,” pointing to crisis and social disruption as drivers of change.39

But its lack of a blueprint was not itself a weakness, for a comprehensive plan would have relegated the project to just another utopian expectation that would fade away, or a bureaucratic formalization that would drain-off creativity. The strength of their approach, instead, was to encourage adaptations and cultural points of entry, producing an evolutionary transformation on multiple levels – call it organic, or local to global. Furthermore, the very fact that an institute of this caliber sponsored such a project lent credibility to the social and spiritual revolution already in motion – a revolution fueled, in large part, by the very personalities who contributed to the report.

The burgeoning New Age community latched on. Mark Satin’s influential book, New Age Politics, referenced the SRI document in making the case for a new ethics.40 Marilyn Ferguson praised the work of Harman and the SRI team, recognizing that their project had “laid the groundwork for a paradigm shift in understanding how individual and social transformation might be accomplished.”41 Her massively influential book, The Aquarian Conspiracy, was simply a repackaging of SRI and what was being fleshed out, in parallel, at the Esalen Institute.42

The SRI team had validated a nebulous idea, a mythic transformation.

Disenchantment portended a new framing story.

Part 3 will explore Re-enchantment as a movement of sacred secularity.

Max Weber, From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology (Oxford University Press, 1946, translated and edited by H.H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills), p.139.

Ibid., p.51, introductory remarks by Gerth and Mills on the role of Schiller. Friedrich Schiller was a playwright, poet, and aesthetic philosopher, forming an important link in the chain of German Romanticism.

Ibid., p.244. See his entire essay, “Bureaucracy,” which makes up chapter 8.

Berman, The Reenchantment of the World, p.190. Berman equates scientific dogma with the prior-held medieval Catholic system.

“But know this, that in the last days perilous times will come: For men will be lovers of themselves, lovers of money, boasters, proud, blasphemers, disobedient to parents, unthankful, unholy, unloving, unforgiving, slanderers, without self-control, brutal, despisers of good, traitors, headstrong, haughty, lovers of pleasure rather than lovers of God, having a form of godliness but denying its power. And from such people turn away!” – 2 Timothy 3:1-5.

See Richard Noll, The Aryan Christ: The Secret Life of Carl Jung (Random House, 1997).

Carl G. Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections (Vintage Books, 1989), p.340.

Rene Dubos, A God Within (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1972), p.251.

John N. Oswalt, The Bible Among The Myths (Zondervan, 2009), p.45.

See Yehezkel Kaufmann, The Religion of Israel: From Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile (The University of Chicago Press, 1960, translated and abridged by Moshe Greenberg), pp.24-44.

Regarding the issue of myth and literary similarities found in the Bible, Oswalt writes: “Are there striking similarities between the Bible and the religion it describes and the ancient Near Eastern literature and the religions found therein? There certainly are, and we should be surprised to find it otherwise. Israel is described in the Bible as a full participant in its world. But what we find is that those similarities are not the defining features of the Bible or of biblical religion. This is unmistakably evident to anyone who takes the Bible as a whole.” The Bible Among The Myths, p.192.

Ibid., p.45.

Ibid., p.46.

Kaufmann, The Religion of Israel, p.29.

Sharon Devlin, as interviewed by Margot Adler, Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today (The Viking Press, 1979), p.138.

Orrin E. Klapp, Ritual and Cult: A Sociological Interpretation (Public Affairs Press, 1956), p.16, italics in original.

Starhawk, The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess (HarperOne, 1999, 20th Anniversary Edition), p.72.

Famed Wiccans, Janet Farrar and Gavin Bone, bring this out in their book, Lifting the Veil: A Witches’ Guide to Trance-Prophecy, Drawing Down the Moon, and Ecstatic Ritual (Acorn Guild Press, 2016). For example, in one interview regarding trance-prophecy, Witch Gede Parma described it thus: “Any vessel who hopes to partner with a deity or spirit in possessory work must know this: both parties must treat the experience as a holy communion – the temple of flesh meeting with the mantle of spirit” (p.54).

Nels and Judy Linde, Taking Sacred Back: The Complete Guide to Designing and Sharing Group Ritual (Llewellyn Publications, 2016), p.19.

Ibid., p.62.

Stephen Larsen, The Mythic Imagination: Your Quest for Meaning Through Personal Mythology (Bantam Books, 1990), p.31. Larsen was a friend to and sat under the teachings of Joseph Campbell, and trained with Stanislav Grof.

See Jacques Ellul, Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes (Vintage Books, 1973, originally published in 1965).

Bill Kinser and Neil Kleinman, The Dream That Was No More a Dream: A Search for Aesthetic Reality in Germany, 1890-1945 (Harper and Row, 1969), p.12.

Ibid., p.13.

Ervin Laszlo, “The Inadequacy of Contemporary Goals – Some Conclusions,” Goals in a Global Community: The Original Background Studies for the Goals for Mankind – A Report to the Club of Rome, Volume II – The International Values and Goals Studies (Pergamon, 1977, edited by Ervin Laszlo and Judah Bierman), p.551.

Anne Corrigan, “Science and Myth: Two Proposals to the Club of Rome,” Goals in a Global Community: The Original Background Studies for the Goals for Mankind – A Report to the Club of Rome, Volume I – Studies on the Conceptual Foundations (Pergamon, 1977, edited by Ervin Laszlo and Judah Bierman), p.305.

Ibid., p.306. The US Office of Education made the request in 1968.

O.W. Markley and Willis W. Harman, Changing Images of Man: Prepared by the Center for the Study of Social Policy/SRI International (Pergamon Press, 1982), p.xvii. Note: This report was completed in 1974 but was not published in a widely distributed format until Pergamon released it in 1982. It was through Ervin Laszlo’s work as editor of the Systems Science and World Order Library: Explorations of World Order, a series under the Pergamon label, that Changing Images of Man was considered for a larger audience.

Harman was introduced to LSD in the late 1950s through Captain Al Hubbard, a renowned figure in the American intelligence community who has been described as the “Johnny Appleseed of LSD.” In the 1960s, Harman was engaged in LSD therapy research via the International Federation for Advanced Studies. See Martin A. Lee and Bruce Shlain, Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD: The CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond (Grove Press, 1992), p.198.

According to Walter Truett Anderson, Harman was the first to give an official lecture at Esalen. See Walter T. Anderson, The Upstart Spring: Esalen and the American Awakening (Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1983), p.68. Anderson details the connection between Esalen and Stanford via Michael Murphy’s experiences at the university, saying, “Much of the credit (or blame) for the birth of Esalen goes to Stanford.” (p.26).

Markley and Harman, Changing Images of Man, pp.vii,xv.

Ibid., p.xix.

Ibid., p.203.

Ibid., p.8, italics in original.

Ibid., p.185.

For extra details on SRI, see Art Kleiner, The Age of Heretics: A History of the Radical Thinkers Who Reinvented Corporate Management (Wiley, 2008, second edition).

Markley and Harman, Changing Images of Man, p.202, italics in original.

Ibid., p.184. The report equated the new vision as “true Freemasonry,” saying there is “one lodge – the universe, and one brotherhood, everything that exists. Each person has the ‘privilege of labor,’ of joining with the ‘Great Architect’ in building more noble structures and thus serving in the divine plan.” The authors believed that by adopting this as a social norm, compatible with “more indigenous” versions from other parts of the world, Americans might discover a renewed sense of meaning in their “technological-industrial thrust” (p.185).

Ibid., p.160.

Mark Satin, New Age Politics: Healing Self and Society (A Delta Book/Dell Publishing, 1979), p.104.

Marilyn Ferguson, The Aquarian Conspiracy: Personal and Social Transformation in the 1980s (J.P. Tarcher, 1980), p.61.

This is my own analysis of Ferguson’s book.