Regionalism and World Order: Part 1

Grand Designs and Utopian Visions

By Carl Teichrib

This is Part 1 of a multi-part series on regionalism within the context of world order, briefly exploring its history, anticipations of a North American Union, the Trump administration and regional rejuvenation, and possible outcomes within the United Nations Security Council.

“The two processes of globalization and regionalization are articulated within the same larger process of global structural transformation…” – Bjorn Hettne.1

“…let us create regional continental units…the European Union, an American Union, which I’ve been pushing too – and this how you got the trade agreement between the US and Canada. And then we’ll take the five continents, and the five continents, if they’re united, will create a World Union.” – Robert Muller.2

With comments from President Trump about Canada amalgamating with the United States — which may have started as a jab against an unpopular Prime Minister Trudeau, but quickly became a more serious talking point — the question of regional integration has once again been raised. Responding to Trump’s statements, well known Canadian investor Kevin O'Leary openly recommended a North American Union, merging the two economies. Much speculation has ensued, along with tariff actions and counter-threats and other tensions as national agendas are jostled by this new administration. Nevertheless, the issue of regionalism has resurfaced, and in some unexpected ways.

Dreams of regional and continental integration are not new. During the earlier quarter of the 19th century, military strategist and independence champion Simón Bolívar envisioned a unified Spanish America, offering proposals for alliances and confederations. In Europe, thought leaders and statesmen have had a long history of envisioning an integrated people: William Penn’s 1693 essay on Europe’s future and Edmund Burke’s Commonwealth of Europe comes to mind.

Then, during-and-after World War I, influential voices advocated for a united Europe. Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi pressed for the creation of the International Pan-european Union. Italian statesman Francesco Nitti wrote of a future European federalism, and French diplomat Aristide Briand made a call for European integration while at the League of Nations in 1929. In America, Nicholas Murray Butler, president of Columbia University and confidant to Andrew Carnegie, argued for a new international order wherein Europe would be refashioned under the “sun of unity.”3

What would this “United States of Europe” portend?

Butler outlined the following in 1914,

“…the time will come when each nation will deposit in a world federation some portion of its sovereignty for the general good. When this happens it will be possible to establish an international executive and international police, both devised for the especial purpose of enforcing the decisions of the international court.”4

However, it wasn’t until World War II that the concept of world federalism seriously emerged as part of the broader discourse. During that horrific conflict, and in the years following, the push for a new internationalism gained traction; politicians, policy organizations, church groups,5 academia, and the public were openly interested in the notion of world government. Regionalism as an important component was being considered.

In 1942, the Washington DC-based Brooking Institute released its report, Peace Plans and American Choices, penned by Arthur C. Millspaugh. What were the choices?

Four main ideas surfaced:

America Alone: As the world’s superpower, “American Mastery” would stress the “economic and military power of the United States, and assumes a frequent, vigilant, and aggressive use of that power to maintain world order.”6

Anglo-American Union: A federal union between the United States and Britain, or an expanded arrangement including the US, Britain, Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa.7

Regionalism: Regional arrangements “as steps or stages in the evolution of a universal world order, as substitutes for a universal order, or as something to be combined with a world-wide system.”8

An international body: Either continue with the League of Nations, or build something more robust, like an international military council acting as a collective authority.9

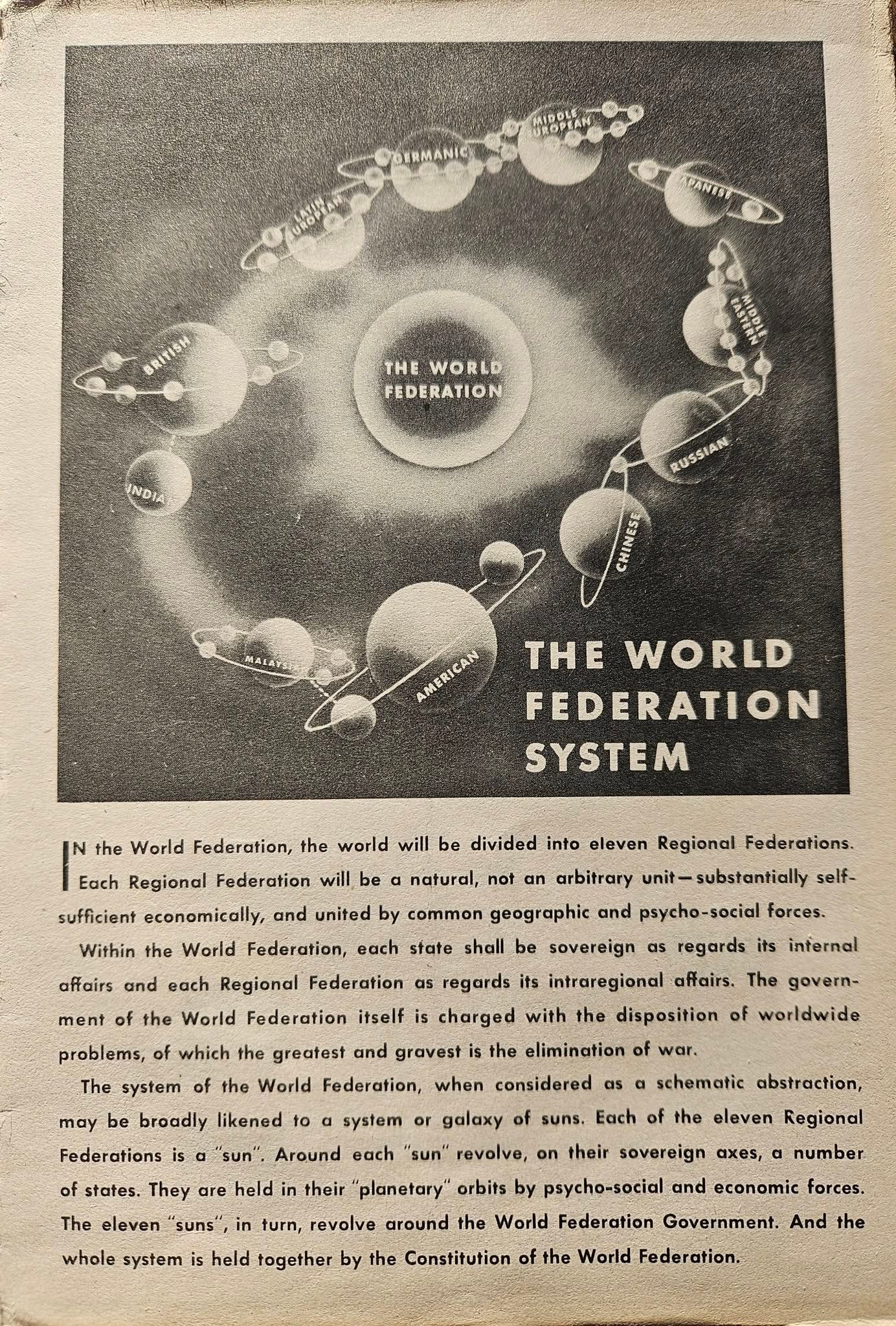

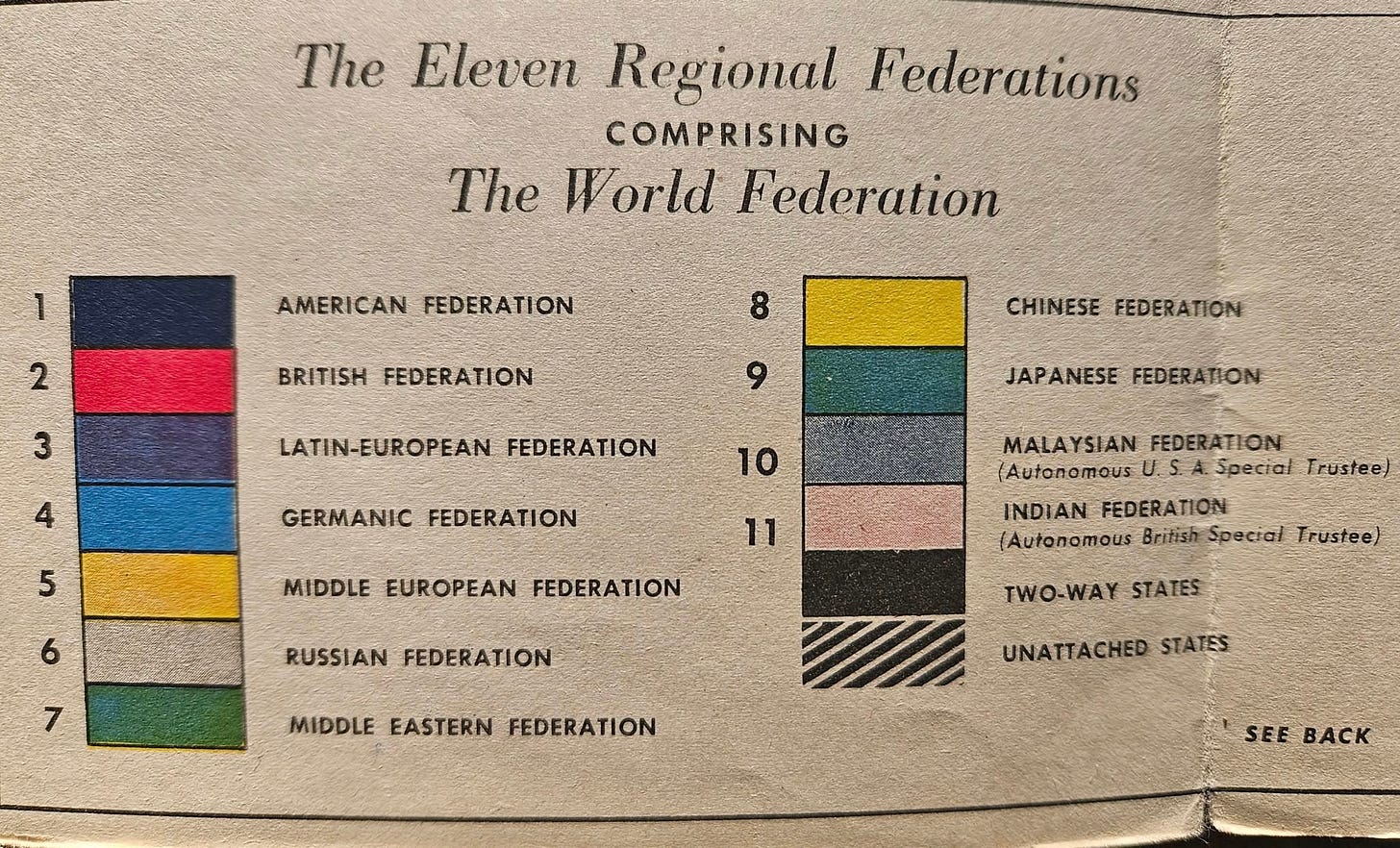

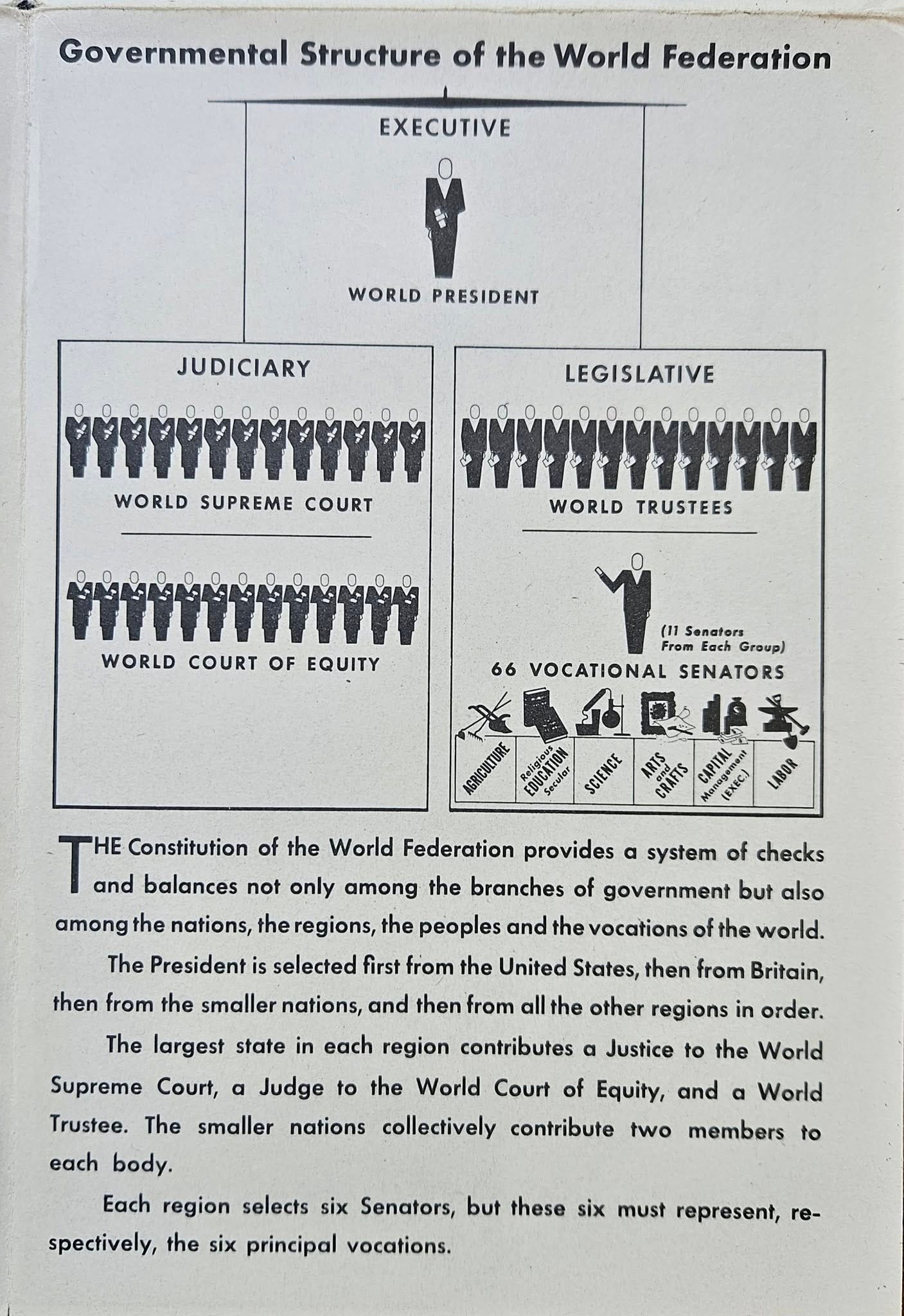

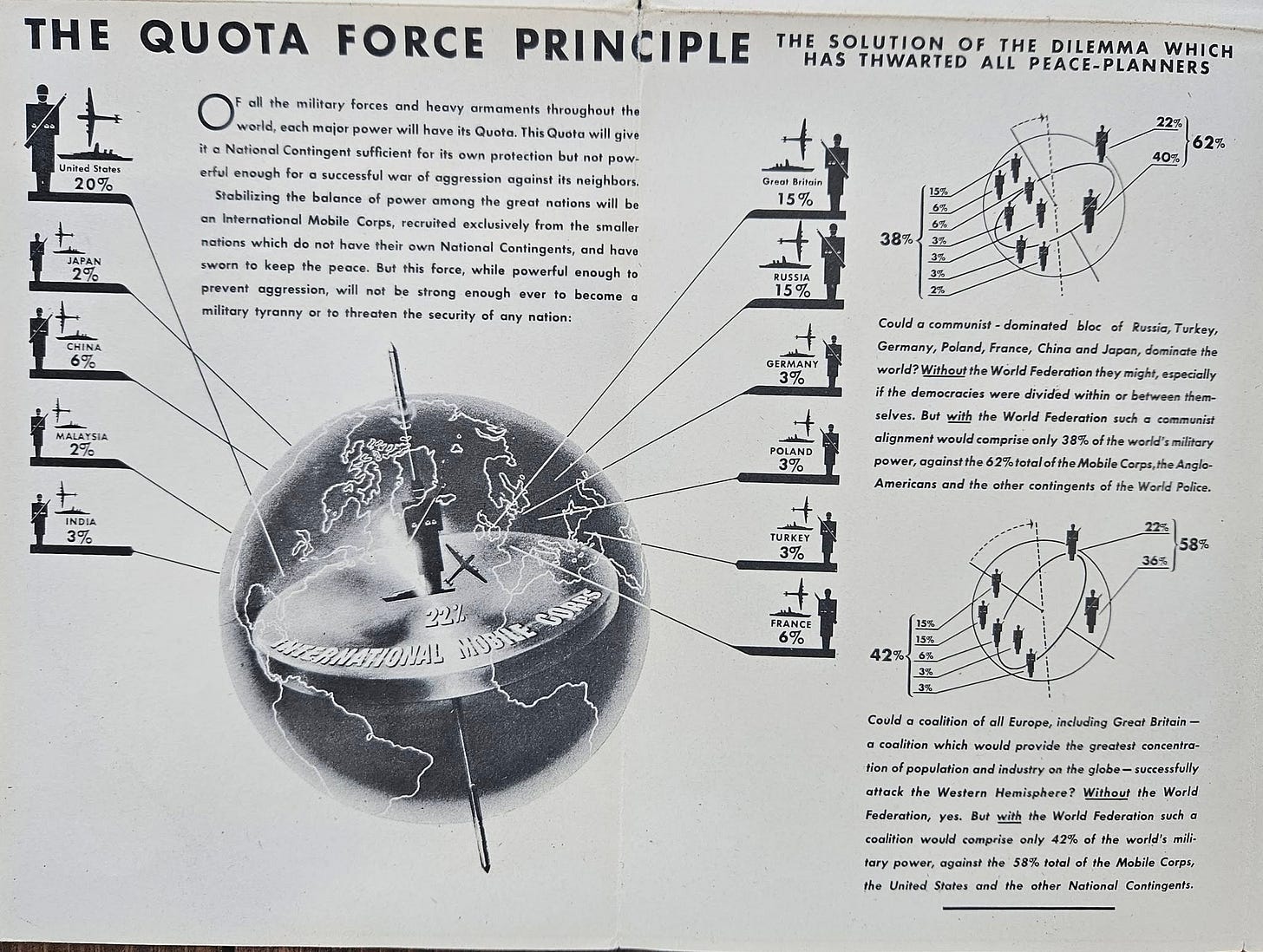

More focused on the regional dimension was the work of Ely Culbertson, a renowned contract bridge player who also studied mass psychology and world systems. His 1943 book, Total Peace, argued for a comprehensive restructuring of the international order, including a proposed constitution for a World Federation. Central to his plan was the development of regions wherein the world would be divided into eleven blocks. Nine regional federations would form the backbone while two national zones – Malaysia and India – would be under the “temporary trusteeship of the United States and Great Britain respectively.”10 In Culbertson’s arrangement, “the World Federation shall come into being when two or more Regional Federations become members.”11 Moreover, these regions would contribute military forces via a quota scheme that would coalesce into a World Police, with the largest nations in each block adding judges to three new bodies, the World Supreme Court, the World Court of Equity, and the World Trusteeship. Smaller nations would “collectively contribute two members to each body.”12

NOTE: The following images are from a loose brochure inserted within Total Peace.

One of the purposes of establishing regions, Culbertson explained, was to enhance the move to a global community. “The world is still too large for a central government to attend to its needs,” the bridge player wrote,

“Without Regional Federations… sovereign nations would continue their semichaotic relations in a climate of quarrels and strife… Nations must learn how to co-operate with their neighbors before co-operating with the world.”13

Obviously his proposal didn’t materialize, but Culbertson’s work was part of that wider movement towards world federalism which flourished during the War years. It was also important in that it specifically detailed regionalism as a keystone of world order.

Another plan for regionalism and world federation was put forward by a respected academic committee. One week after the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Robert M. Hutchins – chancellor of the University of Chicago – began deliberating with colleagues on the question of a world state. The Committee to Frame a World Constitution was born.

As one historian explained,

“That such a constitution could be written by knowledgeable men and women, including a university chancellor, two deans of prominent law schools, a former member of Franklin Roosevelt’s ‘brain trust,’ and leading professors of Chicago, Harvard, Stanford, and Toronto, is a reflection of the more hopeful, politically more imaginative times of the 1940s, particularly after the use of the atomic bomb in 1945.”14

In 1948, Hutchins’ group – loosely known as the “Chicago Committee” – released their Preliminary Draft of a World Constitution. In this scheme the proposed world government would operate with nine electoral regions, sending representatives to a convention that would then “elect 99 world legislators and a president.”15

As it stood, the nine regions – and Committee applied labels – were made up of the following zones:

1) Europe: The European continent, with the UK if it so decides – and with possible inclusion of the English-speaking Commonwealth countries and members of the French Union – but without Russia.

2) Atlantis: United States, with the option of the UK joining the US if so decided. Canada was not listed in the mix, but it would be assumed inside this zone.

3) Eurasia: Russia, with the Baltic and Danubian regions.

4) Afrasia: Middle East and North Africa.

5) Africa, south of the Sahara, with or without South Africa.

6) India, possibly with Pakistan.

7) Asia Major: China, Japan, Korea.

8) Austrasia: South Pacific nations along with Indochina and Indonesia.

9) Columbia: Western Hemisphere south of the United States.

The Chicago Committee’s work received some fanfare, however, by the time the Preliminary Draft was public, the growing Cold War had dampened political appetite, and the project faded. But the dream of international management and collective security hadn’t disappeared. As the 1940s wrapped up and the Cold War decades followed, other world government schemes and plans emerged. Groups like the World Movement for World Federal Government (started in 1947, it today operates as the World Federalist Movement), the World Service Authority (1953), and the World Constitution and Parliament Association (1966)16 helped keep the narrative alive.

In 1947 the World Federalists community released their Montreux Declaration. Regions were suggested, along with the formation of technical groups, as part of an effective world government,

“The formation of regional federations – insofar as they do not become an end in themselves or run the risk of crystallising into blocs – can and should contribute to the effective functioning of federal government. In the same way, the solution of technical, scientific and cultural problems which concern all the peoples of the world, will be made easier by the establishment of specialist functional bodies.”17

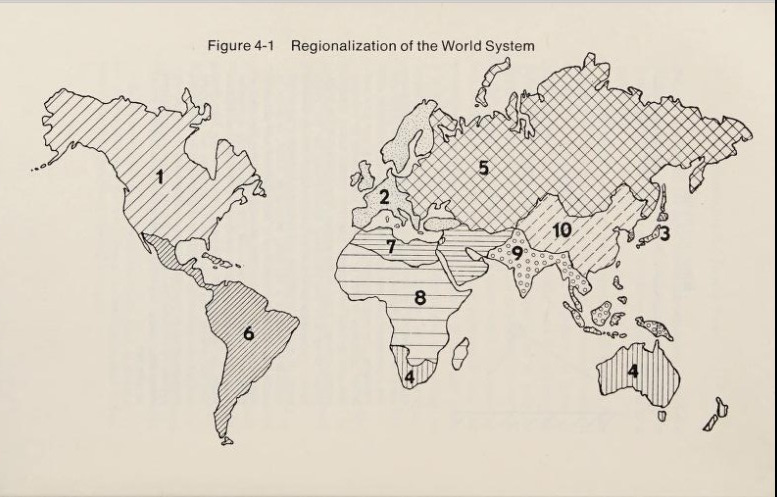

In 1968 a new globalist organization was formed, the Club of Rome, with industrialists, systems scientists, and political personalities filling the ranks. Due to the influence and institutional connections of its members, the Club of Rome quickly gained prominence. In 1974 it released its second report, Mankind at the Turning Point, making the case for the interconnection of global problems and the need for technical policy solutions to avert crisis. It was a call for a New International Order.

Using computer modeling, the Club outlined a regional strategy, dividing the world into ten zones:

1) North America, being the United States and Canada.

2) Western Europe.

3) Japan as a nation/region on its own.

4) Other developed markets; Australia, Israel, New Zealand, Oceania, South Africa, and Tasmania.

5) Eastern Europe, including the Soviet Union.

6) Latin America.

7) North Africa and the Middle East.

8) Main Africa.

9) South/Southeast Asia.

10) Centrally Planned Asia: China, Mongolia, North Korea, and North Vietnam.18

It was understood that, together, these regions would form a world system while maintaining important distinctions,

“The regional view is not antithetical to the concern for comprehensive global development; on the contrary, it is necessary for dealing with the important issues with which the world is and/or will be confronted… It is essential to acknowledge the fact that world community consists of parts whose pasts, presents, and futures are different. Hence, the world cannot be viewed as a uniform whole, but must instead be seen as consisting of distinct, though interconnected, regions.”19

These plans, whether from the Club of Rome or earlier endeavors, placed their delegated regions within the context of an integrated one-world system. The reality, however, turned out to be somewhat different – thanks to the Cold War and concerns over the growing threat of Communism.

Instead of zones forming to specifically advance world federalism, regional and multilateral alliances were constructed around more pragmatic Cold War realities and trade/development blocs: NATO (1948), the European Coal and Steel Community (1952), the Warsaw Pact (1955), and ASEAN (1967). These bodies, like the Arab League (1945), served different functions than envisioned by world government maximalists, even if some – like NATO to a degree, and especially the ECSC – had connections to the broader hope of world unity.20 Later would come the Caribbean Community (1973), the Gulf Cooperation Council (1981), the Commonwealth of Independent States (1991), the European Union (1993), the African Union (2002), and the South American blocs of Mercosur (1991) and UNASUR (2004), among other economic cooperation zones.

But what about North America?

Carl Teichrib is the author of Game of Gods: The Temple of Man in the Age of Re-Enchantment. See chapter 11 — “The Cult of World Order” — for an in-depth exploration of world federalism.

Björn Hettne, “Globalization, the New Regionalism and East Asia,” Globalism and Regionalism (Selected Papers Delivered at the United Nations University Global Seminar '96, Shonan Session, 2-6 September 1996, Hayama, Japan).

Robert Muller, speech before the Global Citizenship 2000 Youth Congress, April 5, 1997, Vancouver, BC. An audio tape of his speech, along with the entire event, is in the author’s possession.

Nicholas Murray Butler, A World in Ferment: Interpretation of the War for a New World (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1918), p.31.

Ibid., p.36.

The Federal Council of Churches had a special committee on world order, led by John Foster Dulles. Furthermore, the Methodist Council of Bishops held a “Crusade for a New World Order,” and the Northern Baptist Convention had initiated a “World Order Crusade.” In 1946, the Southern Baptist Convention issued a statement supporting world federation and empowering the United Nations.

Arthur C. Millspaugh, Peace Plans and American Choices (The Brookings Institute, 1942), p.15-16.

See chapter 3.

Ibid., p.49.

See chapters 5 and 6.

Ely Culbertson, Total Peace: What Makes Wars and How to Organize for Peace (Doubleday, 1943), p.253.

Ibid., p.260.

Culbertson, Total Peace insert brochure titled The World Federation System.

Culbertson, Total Peace, p.313.

Joseph P. Baratta, The Politics of World Federation: From World Federalism to Global Governance (Praeger, 2004), p.316.

Ibid., p.315-316.

The WCPA was birthed through an earlier organization called the U.S. Committee for a World Constitutional Convention.

A copy of the Montreux Declaration can be found here: www.wfm-igp.org/about-us/montreux-declaration.

Mihajlo Mesarovic and Eduard Pestel, Mankind at the Turning Point (E.P. Dutton, 1974), pp.161-164.

Ibid., pp.39-40.

The formation of NATO overlapped with the ideas of Clarence Streit, whose Union Now plan envisioned America forming a tight alliance with Britain and other Western democracies. And the development of the ECSC – leading up to the EU – was grounded upon visions of European federalism, itself tied to hopes of one-world. For example, the 1946 Hertenstein Programme stated, “A European Community on federal lines is a necessary and essential contribution to any world union.” In 1947, Winston Churchill made the following statement at Albert Hall, London, “But let there be no mistake upon the main issue. Without a United Europe there is no sure prospect of world government. It is the urgent and indispensable step towards the realisation of that ideal.”