The Not-So-Magic Bus Ride:

Road Tripping to a New Worldview

By Carl Teichrib

This past June I attended Psychedelic Science 2025, the largest event of its kind this year. One take-away was that, for all the talk of therapeutics and neuroscience and chemistry and clinical trials, there was an undeniable – in fact, a consistently reinforced – connection to experiential spirituality. The age of scientific determinism and materialism is shifting, I was told, towards an era wherein the technical is intentionally blended with the mystical. In my book, Game of Gods, I describe this as an “ancient-future worldview.”

PS2025 also continuously paid homage to its counter-cultural roots. From often-made references highlighting the 1960s, to Timothy Leary name-dropping, to a shrine venerating Ram Dass, the linkage was clear and celebrated.

With both points in mind, I have decided to refresh a section from my book and post it for your use. I trust it will be beneficial as you watch the cultural tsunami take shape, and that it will act as a reference to better understand the historical context of this approaching “new worldview.”

Finally, one of the reports often mentioned at PS2025 was the freshly released Johns Hopkins research paper, Effects of Psilocybin on Religious and Spiritual Attitudes and Behaviors in Clergy from Various Major World Religions. Recently, a whistleblower on the Johns Hopkins project – Joe Welker – kindly reached out to me, pointing to his extensive analysis of this important development. I would strongly encourage you to check out Joe’s work here: www.psychedeliccandor.org.

For more on PS2025, see Where There Is Smoke. And for background on the spiritual dimension of the psychedelic narrative, see Psychedelic Spirituality.

The summer of 1964 witnessed an unusual, all-American road tour.

Ken Kesey — an athletic young man with a flamboyant personality — assembled his Merry Band of Pranksters, an eclectic group of friends and free spirits. Together, in a wildly painted International Harvester school bus playfully named Furthur, they tripped across the United States in a psychedelic assemblage, spreading the seeds of a new culture. It was, as some would later call it, “the great freak forward,”1 and it would leave an indelible mark on the nation.

Just four years earlier, Kesey was a student in Stanford University’s creative writing program, working on what would become his landmark novel, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Looking to make extra money, his friend, Vic Lovell told him about a drug trial at Menlo Park Veterans Hospital. Volunteers were being paid $75 a session to serve as test subjects for a government-funded investigation into the effects of mescaline, psilocybin and LSD. Unbeknownst to the human guinea pigs, this clinical study was part of the Central Intelligence Agency’s MK-Ultra program, a covert mind-control and drug experiment effort.2

Kesey, however, didn’t just undergo the tests – he flipped the script. He soon took a night job at the same hospital, surreptitiously gaining access to the psychiatric ward’s drug supply, specifically with an eye towards liberating the lysergic acid diethylamide. LSD, which Kesey had experienced under the controlled experimentation of CIA-linked clinicians, would freely flow beyond the walls of the hospital.

Now a celebrated author, Kesey became the gravitational center of a swirling collective of psychedelic experimenters. A host of personalities entered his orbit. Allen Ginsberg and “Zen lunatic”3 Neal Cassady — both legendary figures from the Beat Generation — were part of the scene. So too was Timothy Leary’s friend and Harvard collaborator, Richard Alpert (later known as Ram Dass) and, at the cultural fringes, the gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson. Academics from Stanford and Berkeley rubbed shoulders with the acid-heads, and with the Hells Angels, who famously partied with the Pranksters. In the mix was a local band called The Warlocks, soon to be reintroduced to the world — at a Prankster event — as The Grateful Dead.4

What solidified Kesey’s place in the nation’s social history, however, was a monumental, living Happening. A core group of his Pranksters did the unthinkable; they took the psychedelic experience to main-street USA. In 1964, the great American road trip became the outrageous American acid trip.

Starting in La Honda, California, Kesey and his Pranksters set off across the country in their kaleidoscopic-painted bus – arguably, the first art car. On the back was a sign, “Caution: Weird Load.” Already outfitted with beds, kitchen and restroom, the bus was upgraded with an external loudspeaker, a roof-mounted sitting deck with an access port, and copious amounts of mind-altering drugs. New names and personas were assumed, and the rowdy crew followed the experience where it took them. It was a psychedelic trip on wheels, and the United States was the set-and-setting.

Parading into small towns and big cities with the loudspeaker blaring and public antics to match, the Merry Pranksters would inevitably draw a crowd. Such a sight had never been seen before; such ideas were novel and shocking. People were stunned by the spectacle, having been, in effect, psychologically jolted. A film camera captured the coast-to-coast chaos — the Pranksters weren’t just recording a movie; they were living in one. It was a pressure-cooker experience: Drugs, sex, rock and roll, and shock-induced insanity in a multi-colored, rolling can. The gospel of acid had been preached.

The trip itself had been a circuitous route: Phoenix, Houston, New Orleans, Pensacola, and then up to New York City. They stopped at Timothy Leary’s mansion-commune in Millbrook, where the East-coast guru had set up his League for Spiritual Discovery.5 Turning westward, they traversed the US Midwest before angling up to Alberta where the Pranksters attended the Calgary Stampede. There, in a move that would later stir controversy, they picked up a 15-year-old girl, deceived the police who were looking for the run-away, and took her to California. Soon after returning to La Honda, a jaunt was made to the Esalen Institute where their leader gave a seminar titled, “A Trip with Ken Kesey.”6

Upon returning west, the cultural landscape they had helped shape was already beginning to bloom in San Francisco, and the nation was stirring.

America had just been initiated.

For a snap-shot into the world of MK-Ultra, Kesey and the 1960s, and the disturbing world of psychedelic mind experiments — and more — here’s an NPR interview with journalist and author Stephen Kinzer: The CIA's Secret Quest For Mind Control: Torture, LSD And A 'Poisoner In Chief.’

Happenings of Change:

A cultural crossover was happening in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco. What had been a local haven for Beats was now feeling the influx of the burgeoning Hippie movement. Energized by the music scene emanating, largely, from Los Angeles’ Laurel Canyon and Sunset Strip, and turned-on by the Bay Area’s psychedelic wave, the Hippie attitude was one of “good times and good feelings.”7 The Hippies celebrated in the “spirit of medieval fairs,” while the Beats tended to isolate themselves; the Beats listened to folk and jazz, but the “Hippies wanted to dance.”8

And dance they did.

On October 16, 1965, in San Francisco’s Longshoreman’s Hall, a concert party organized by Chet Helms and his art commune, Family Dog, managed to produce a kind of social magic. Pranksters, psychedelic rockers, Beats and Hippies, gelled in a trance-state of dance and drug-induced ecstasy.

“Those in attendance that night sensed that the forces of the Haight scene had converged into something powerful,” writes historian Mark H. Lytle. “Kesey saw in that gathering a way to further his quest to turn on the masses.”9

Kesey put in motion his Acid Tests, the method through which the feeling could be reproduced. From late 1965 until the end of March 1966 the Pranksters conducted Acid Tests in the Bay Area, Portland, and Los Angeles. These were semi-public LSD parties advertised with the challenge: “Can you pass the Acid Test?”

In White Hand, a history of Timothy Leary’s relationship with Beat poet and Prankster, Allen Ginsberg, author Peter Conners gives this explanation,

The Acid Tests were LSD-fueled sensory assaults of music, dance, art, and extravagant weirdness that were meant to, as the title implies, ‘test’ the trippers’ psyches under extreme conditions. Unlike Leary’s experiments, the Acid Tests weren’t about visionary revelation or self-realization for the participants: they were more about releasing cosmic tension and upending the confines of constricting societal mores.10

“The Acid Tests were one of those outrages,” penned Tom Wolfe in his famous telling of the Kesey episode, “one of those scandals, that create a new style or a new world view.”11

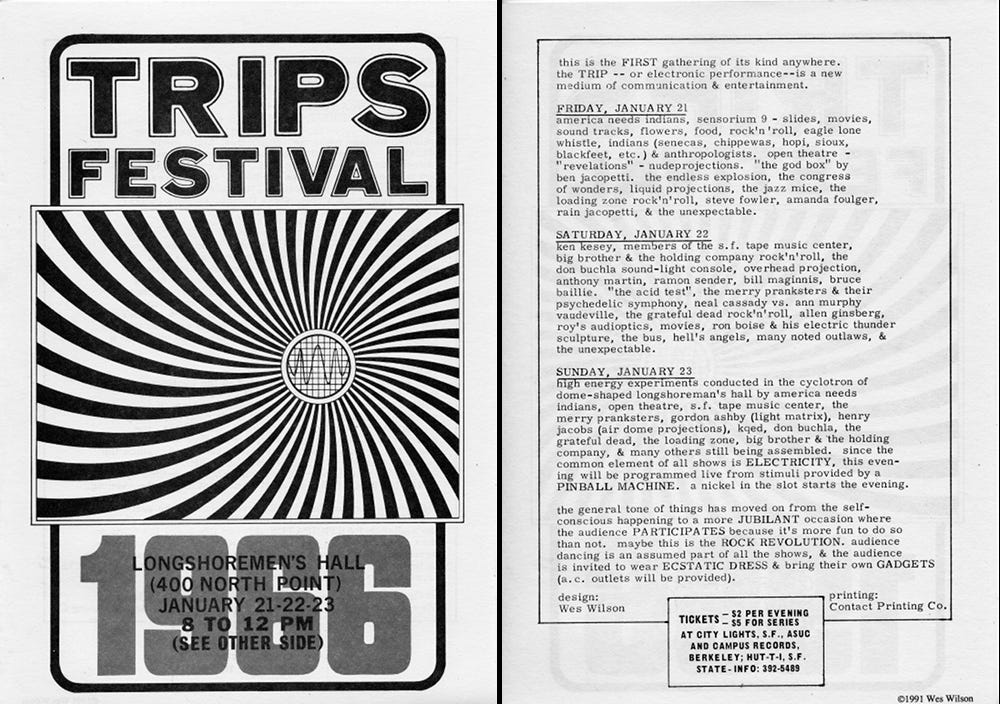

The Acid Test extravaganza, the one that set the counterculture in high gear, took place on the second-last weekend of January 1966. This was the Trips Festival held in Longshoreman’s Hall, near San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf. Hosted by the Pranksters and their friend, Stewart Brand – who, like Kesey, had been turned-on to LSD through MK-Ultra, and who later published the Whole Earth Catalog – Trips was a three-day blowout attended by 6,000 to 10,000 people.

It was a drug-induced, multi-media, sensory-overloaded, display of boundary dissolving insanity,

…with just about every sight and sound imaginable: mime exhibitions, guerrilla theater, a ‘Congress of Wonders,’ and live mikes and sound equipment for anyone to play with. Closed-circuit television cameras were set up on the dance floor so people could watch themselves shake and swing. Music blasted at ear-splitting volumes while Day-Glo bodies bounced on trampolines. At one point Kesey flashed from a projector, ‘Anyone who knows he is God please go up on stage.’12

Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead tried to describe the madness: “Thousands of people man, all helplessly stoned, all finding themselves in a room of thousands of people, none of whom any of them were afraid of. It was magic, far out beautiful magic.”13

The Trips Festival was not a concert. Rather, Trips acted as an immersive experience combining media technologies, music and dance, art and performance. It was celebration, transgression, and absurdity with a spiritual feeling of connection. In terms of Western evolutionary culture, Trips was the first transformational festival.

The following year, now on the other side of California’s prohibition of LSD, San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park was home to the Human Be-In. Unlike Trips, this festival was an outdoors event, portrayed as a gathering of the tribes; the idea being that Western civilization must embrace a tribal system,14 and counter-culture factions – Berkeley activists, Beats and Hippies – needed to merge in a “new and strong harmony.”15 Exact number of attendees remains unknown, but it is estimated that 20,000 to 30,000 people came for the love-in.

It was a poorly planned and loosely assembled event. Organizers were debating the night before over how much time should be given to speakers such as Timothy Leary, and one person suggested moving it from Golden Gate Park to the beach for a “groovy naked swim-in.”16 It stayed in the Park, and the music was provided by the likes of Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead. Eastern spirituality and political activism were sermonized for the crowds. Most of all, the Be-In was about being together: being in solidarity, in community, and being present in the change.

The Los Angeles Free Press, covering its own city’s much smaller Be-In, also published a report describing the San Francisco vibe,

‘Welcome,’ said a calm voice from the platform. ‘Welcome to the first manifestation of the Brave New World.’ And a kind of collective sigh came over the audience. Could this be true, could it be really true? Here we were 20,000 blown minds together – gathering for nothing more than love and joy, to celebrate our oneness...17

Beat-Prankster-Hippie-Activist, Allen Ginsberg, played a major role in setting the spiritual tone. He was poetical, experimental, and mystical.18 Timothy Leary famously roused the masses with his signature motto: “The only way out, is in. Turn on, tune in, and drop out.”19

Beat poet Lenore Kandel imparted Eastern philosophy to the gathering,

The Buddha, who will reach us all, through love: not through doctrine, not through teachings, but through love. And, as I’m looking at all of you – all of us – I feel more and more that Maitreya is not this time going to be born in one physical body, but born out of all of us… This is an invocation for Maitreya, may he come: To invoke the divinity of man, through the mutual gift of love…20

Ron Thelin, co-owner of The Psychedelic Shop in Haight-Ashbury, the first retail outlet for drug paraphernalia in the United States, described the Pied- Piper effect of the Be-In: “It was like this calling, like a conch shell blowing, ‘Hey’ – from an ancient time – ‘Come out, come back, re-appear; all you Gods and Goddesses, you divine people, home, come’.”21

Not all shared the hype. The Berkeley Barb was critical in its follow-up, saying the Be-In was a waste of time; “the worst thing of all was the emptiness of the speakers, the lack of anything going on.”22

Although the event was an organizational mess, it sparked a vision. The Be-In was a conch shell blowing, and tens of thousands of young people flocked to San Francisco in what became the Summer of Love.23 But along with the human inflow came added social problems, and hard drugs flooded the streets of Haight-Ashbury. While psychedelic visionaries were proselytizing collective unity and spiritual oneness, an increase in violent crime quickly marked the “acid ghetto.” In the ugly wake of the “good vibes” came a trail of human wreckage.24

Nevertheless, a string of concert festivals emerged after the Human Be-In, each a container of celebration for the growing counterculture. The Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Festival incorporated artistic Happenings and music acts, and the Monterey Pop Festival set a new standard for large concert gatherings. The iconic event of the 1960s, of course, was Woodstock with 400,000 partiers.25

Social historian Lytle writes,

If the music brought the fans to Woodstock, the crowd stole the show... So widespread was the sense of community that people began to see themselves as the ’Woodstock Nation,’ suffused in peace and harmony.

Many people came away persuaded that Woodstock signaled a revolution in consciousness. The counterculture was winning the struggle for the nation’s soul.26

However, a few months later the Altamont Free Festival – a West coast attempt at the Woodstock vibe – turned violent and deadly. As the Rolling Stones performed Sympathy for the Devil, 18-year old Meredith Hunter approached the stage with a gun and was subsequently stabbed to death by a member of the Hell’s Angels security team. Altamont graphically signaled the result of a “do what thou wilt” society. One observer wrote, “Woodstock is the potential but Altamont is the reality.”27

The Acid Tests had set minds and spirits in motion. Trips energized the mood. The Human Be-In had rooted the movement, and music festivals functioned as celebratory and transgressive models of realignment.

The counterculture remained in motion after the 1960s, but it was changing – in part because of the negative impact of the drug scene, the commercialization of the vibe, an eroding national economy, and domestic dissent over the Vietnam War.28 San Francisco was still home to novel artistic expressions, radical social ideas and alternative lifestyle communities, setting the stage for later manifestations like the Suicide Club and Cacophony Society, the bizarre experiences of the Jejune Institute, and of course, Burning Man – itself a contemporary Prankster-like event.

With the backdrop of the 1960s in mind, French social critic and theologian, Jacques Ellul, made the following observation,

Music, drugs, incense, violence, sexual freedom: festival… The desire is to get one’s bearings, and to establish an intervening space foreign to the rest of the world, an ocean in which to plunge without restraint, so as to blot out everything which is not the festival. The festival, greatly longed for by all the contestants as a way of putting down modern society, is acclaimed as an ought-to-be, and as the revolutionary means par excellence.

Here it is, put into actual practice. It is already experienced, sometimes as a way of creating the new life, sometimes as a political method…29

Modern Dionysian Man transgresses moral sensibilities while affirming an alternative set of final values: “This call for festival is nothing more or less than a deep religious seething discharging its lava.”30

America’s counterculture was primarily a spiritual revolution.

Carl Teichrib is the author of Game of Gods: The Temple of Man in the Age of Re-Enchantment, a detailed exploration of cultural-religious-political changes and the challenge to Christianity.

Endnotes:

Martin A. Lee and Bruce Shlain, Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD: The CIA, The Sixties, and Beyond (Grove Press, 1992), p.121.

Peter Conners, White Hand Society: The Psychedelic Partnership of Timothy Leary and Allen Ginsberg (City Light Books, 2010), p.166. On MK-ULTRA and mind control, see John Marks, The Search for the Manchurian Candidate: The CIA and Mind Control – The Secret History of the Behavioral Sciences (W.W. Norton & Company, 1979/1991); Don Gillmor, I Swear By Apollo: Dr. Ewen Cameron and the CIA-Brainwashing Experiments (Eden Press, 1987); and Harvey Weinstein, A Father, a Son and the CIA (James Lorimer & Company, 1988). The United States General Accounting Office published the following in Human Experimentation: An Overview on Cold War Era Programs (GAO/T-NSIAD-94-266): “our review... identified hundreds of tests and experiments in which hundreds of thousands of people were used as subjects. Some of these tests and experiments involved the intentional exposure of people to hazardous substances such as radiation, blister and nerve agents, biological agents, LSD, and phencyclidine. These tests and experiments were conducted to support weapon development programs, identify methods to protect the health of military personnel against a variety of diseases and combat conditions, and analyze U.S. defense vulnerabilities. Healthy adults, children, psychiatric patients, and prison inmates were used in these tests and experiments” (p.3). On page 6: “from 1953 to about 1964, the CIA conducted a series of experiments called MKULTRA to test vulnerabilities to behavior modification drugs. As part of these experiments, LSD and other psychochemical drugs were administered to an undetermined number of people without their knowledge or consent.”

Lee and Shlain, Acid Dreams, p.123.

Andrew Grant Jackson, 1965: The Most Revolutionary Year in Music (Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press, 2015), p.252.

Tom Wolfe, author of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, describes the Millbrook encounter in a negative light. However, Graham St. John offers a congenial version in his Mystery School in Hyperspace (pp.59-61).

Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, p.119.

Mark Hamilton Lytle, America’s Uncivil Wars: The Sixties Era from Elvis to the Fall of Richard Nixon (Oxford University Press, 2006), p.204.

Ibid., p.204.

Ibid., p.205. For more on this event, see Lee and Shlain, Acid Dreams, pp.142-143.

Peter Conners, White Hand Society: The Psychedelic Partnership of Timothy Leary and Allen Ginsberg (City Light Books, 2010), p.34.

Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, p.250, italics in original.

Lee and Shlain, Acid Dreams, p.143.

Quoted by Lee and Shlain, Acid Dreams, pp.143-144.

Oliver Johnson, “Pow-Wow,” The Los Angeles Free Press, January 20, 1967, p.3.

“The Beginning is the Human Be-In,” Berkeley Barb, January 6, 1967, p.1.

Conners, White Hand Society, p.201.

Oliver Johnson, “Pow-Wow,” The Los Angeles Free Press, January 20, 1967, p.3.

See the event video at Open Culture, “Rare Footage of the Human Be-In, the Landmark Counter-Culture Event Held in Golden Gate Park, 1967,” (www.openculture.com/ 2014/09/rare-footage-of-human-be-in.html). Peter Conners’ White Hand Society details Ginsberg’s organizational role.

Conners, White Hand Society, p.204.

Excerpted from video footage of the Human Be-In.

Ron Thelin, interviewed in the documentary, Sgt. Pepper: It Was Twenty Years Ago Today, aired on KCET Los Angeles, 1987, video on file.

“The Beginning is the Human Be-In,” Berkeley Barb, January 6, 1967, p.4.

Jean-Francois Revel writes, “In 1967… the hippie population of San Francisco was about 300,000, and San Francisco’s total population at the time was less than 750,000.” Revel, Without Marx or Jesus (Doubleday and Company, 1970/1971), p.208.

Lee and Shlain, Acid Dreams, pp.186-193.

Sheldon Chartier, a personal friend, wandered into Woodstock from the event’s backside. He was 14-years old, visiting a neighboring farm, and could hear music from across the field. Curious as to what was happening, he – with his 9-year old brother in tow, and all following the farmer’s teenage daughter – walked through the crops and into the festival. Sheldon described his multi-day experience as terrifying, chaotic, and magical.

Lytle, America's Uncivil Wars, p.335.

As quoted by George McKay, Senseless Acts of Beauty: Cultures of Resistance since the Sixties (Verso, 1996), p.14.

Lytle, America’s Uncivil Wars, p.338.

Jacques Ellul, The New Demons (The Seabury Press, 1975), p.142.

Ibid., p.143. Around the same time, Jean-Francois Revel wrote, “a ‘revolutionary situation’ exists when, in every cultural area of a society, old values are in the process of being rejected, and new values have been prepared, or are being prepared, to replace them.” Revel, Without Marx or Jesus (Doubleday and Company, 1970/1971), p.9.